Go  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| A day late, and a dollar short  |

Is there such a thing as Fentanyl laced marijuana? ____________________________ NRA Life Member, MGO Annual Member | |||

|

Irksome Whirling Dervish |

I have family that is involved on the enforcement side of the drug trade. In no order this is what's going on: 1. Opioids from dirty doctors is better than it was a year or so ago. Still bad but doctor's are getting the message. 2. China promised the US that it would not directly sell the ingredients to make Fentanyl in the US. No more container ships, false panel containers and so on. They pretty much have kept that promise - and then turned around and openly sell the same ingredients to Mexico. China does it on purpose since they like a weak US citizenry and aren't upset that we're losing quite a few people to this one drug alone. 3. There are 100k drug deaths a year. No one gives a rat's ass about it like they should. It's 100k people and it far surpasses firearms deaths and auto deaths. The 100k number is climbing every year. 3. Social media is a bad thing because that's how your kids buy them, delivered to the front door disguised as something else. The sellers disguise the name of the product and now have created emojis instead so the words never appear. They are creative. 4. If you see a pill marked M30 and there is no'script for it, it's probably laced with Fentanyl. The most common Oxy is impressed with M30 and the drug producers mark theirs the same way to lead the unsuspecting to think the are purchasing legit Oxy. 5. Your local street dealer likely isn't the producer and he probably doesn't know the drugs he's selling are laced. It's bad for business if word gets out that his customers are dying from bad drugs. Some do know and don't care thinking that another druggie will take his or her place but most don't know until you see a rash of deaths or ODs. 6. The producers all want to have the "wow" product and Fentanyl is cheap and gives that punch that is marketable. "My stuff is more potent than the next dealers stuff." 7. It's very hard to prosecute dealers in state court on murder charges because in almost every jurisdiction you have to prove intent for murder. Fed law only requires that you distribute or sell resulting in death to make a murder charge stick. Intent doesn't matter and it's almost strict liability. States are trying to work around this to be more federal like on the charges. 8. In the future if you want to make money - legal money - in the drug business invest in rehab facilities. Lots of money on the state and federal level is coming to tackle the rehab and recovery and since you can't fully cure someone of their addiction with a typical 30 days cycle, many cycles are required. Lather, Rinse, Repeat. | |||

|

| Member |

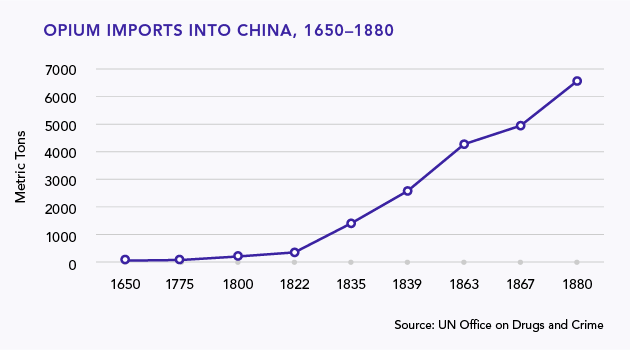

Nations undermining other nations by addicting their citizens has been going on for centuries.Doesn't make it right,but it is reality.And China does know it is weakening us. THE OPIUM WARS IN CHINA https://asiapacificcurriculum....ule/opium-wars-china OVERVIEWDOWNLOAD AS PDF The Opium Wars in the mid-19th century were a critical juncture in modern Chinese history. The first Opium War was fought between China and Great Britain from 1839 to 1942. In the second Opium War, from 1856 to 1860, a weakened China fought both Great Britain and France. China lost both wars. The terms of its defeat were a bitter pill to swallow: China had to cede the territory of Hong Kong to British control, open treaty ports to trade with foreigners, and grant special rights to foreigners operating within the treaty ports. In addition, the Chinese government had to stand by as the British increased their opium sales to people in China. The British did this in the name of free trade and without regard to the consequences for the Chinese government and Chinese people. The lesson that Chinese students learn today about the Opium Wars is that China should never again let itself become weak, ‘backward,’ and vulnerable to other countries. As one British historian says, “If you talk to many Chinese about the Opium War, a phrase you will quickly hear is ‘luo hou jiu yao ai da,’ which literally means that if you are backward, you will take a beating.”1 Two Worlds Collide: The First Opium War In the mid-19th century, western imperial powers such as Great Britain, France, and the United States were aggressively expanding their influence around the world through their economic and military strength and by spreading religion, mostly through the activities of Christian missionaries. These countries embraced the idea of free trade, and their militaries had become so powerful that they could impose such ideas on others. In one sense, China was relatively effective in responding to this foreign encroachment; unlike its neighbours, including present-day India, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia), Indonesia, and Vietnam, China did not become a full-fledged, formal colony of the West. In addition, Confucianism, the system of beliefs that shaped and organized China’s culture, politics, and society for centuries, was secular (that is, not based on a religion or belief in a god) and therefore was not necessarily an obstacle to science and modernity in the ways that Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism sometimes were in other parts of the world. But in another sense, China was not effective in responding to the “modern” West with its growing industrialism, mercantilism, and military strength. Nineteenth-century China was a large, mostly land-based empire (see Map 1), administered by a c. 2,000-year-old bureaucracy and dominated by centuries old and conservative Confucian ideas of political, social, and economic management. All of these things made China, in some ways, dramatically different from the European powers of the day, and it struggled to deal effectively with their encroachment. This ineffectiveness resulted in, or at least added to, longer-term problems for China, such as unequal treaties (which will be described later), repeated foreign military invasions, massive internal rebellions, internal political fights, and social upheaval. While the first Opium War of 1839–42 did not cause the eventual collapse of China’s 5,000-year imperial dynastic system seven decades later, it did help shift the balance of power in Asia in favour of the West. Opium and the West’s Embrace of Free Trade In the decades leading up to the first Opium War, trade between China and the West took place within the confines of the Canton System, based in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou (also referred to as Canton). An earlier version of this system had been put in place by China under the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), and further developed by its replacement, the Qing Dynasty, also known as the Manchu Dynasty. (The Manchus were the ethnic group that ruled China during the Qing period.) In the year 1757, the Qing emperor ordered that Guangzhou/Canton would be the only Chinese port that would be opened to trade with foreigners, and that trade could take place only through licensed Chinese merchants. This effectively restricted foreign trade and subjected it to regulations imposed by the Chinese government. For many years, Great Britain worked within this system to run a three country trade operation: It shipped Indian cotton and British silver to China, and Chinese tea and other Chinese goods to Britain (see Map 2). In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the balance of trade was heavily in China’s favour. One major reason was that British consumers had developed a strong liking for Chinese tea, as well as other goods like porcelain and silk. But Chinese consumers had no similar preference for any goods produced in Britain. Because of this trade imbalance, Britain increasingly had to use silver to pay for its expanding purchases of Chinese goods. In the late 1700s, Britain tried to alter this balance by replacing cotton with opium, also grown in India. In economic terms, this was a success for Britain; by the 1820s, the balance of trade was reversed in Britain’s favour, and it was the Chinese who now had to pay with silver. The Scourge and Profit of Opium The opium that the British sold in China was made from the sap of poppy plants, and had been used for medicinal and sometimes recreational purposes in China and other parts of Eurasia for centuries. After the British colonized large parts of India in the 17th century, the British East India Company, which was created to take advantage of trade with East Asia and India, invested heavily in growing and processing opium, especially in the eastern Indian province of Bengal. In fact, the British developed a profitable monopoly over the cultivation of opium that would be shipped to and sold in China. By the early 19th century, more and more Chinese were smoking British opium as a recreational drug. But for many, what started as recreation soon became a punishing addiction: many people who stopped ingesting opium suffered chills, nausea, and cramps, and sometimes died from withdrawal. Once addicted, people would often do almost anything to continue to get access to the drug. The Chinese government recognized that opium was becoming a serious social problem and, in the year 1800, it banned both the production and the importation of opium. In 1813, it went a step further by outlawing the smoking of opium and imposing a punishment of beating offenders 100 times. In response, the British East India Company hired private British and American traders to transport the drug to China. Chinese smugglers bought the opium from British and American ships anchored off the Guangzhou coast and distributed it within China through a network of Chinese middlemen. By 1830, there were more than 100 Chinese smugglers’ boats working the opium trade. This reached a crisis point when, in 1834, the British East India Company lost its monopoly over British opium. To compete for customers, dealers lowered their selling price, which made it easier for more people in China to buy opium, thus spreading further use and addition. In less than 30 years—from 1810 to 1838—opium imports to China increased from 4,500 chests (the large containers used to ship the drug) to 40,000. As Chinese consumed more and more imported opium, the outflow of silver to pay for it increased, from about two million ounces in the early 1820s to over nine million ounces a decade later. In 1831, the Chinese emperor, already angry that opium traders were breaking local laws and increasing addiction and smuggling, discovered that members of his army and government (and even students) were engaged in smoking opium. The Users Versus Pushers Debate By 1836, the Chinese government began to get more serious about enforcing the 1813 ban. It closed opium dens and executed Chinese dealers. But the problem only grew worse. The emperor called for a debate among Chinese officials on how best to deal with the crisis. Opinion were polarized into two sides. One side took a pragmatic approach (that is, an approach not focused on the morality of the issue). It focused on targeting opium users rather than opium producers. They argued that the production and sale of opium should be legalized and then taxed by the government. Their belief was that taxing the drug would make it so expensive that people would have to smoke less of it or not smoke it at all. They also argued that the money collected from taxing the opium trade could help the Chinese government reduce revenue shortfalls and the outflow of silver. Another side vehemently disagreed with this ‘pragmatic’ approach. Led by Lin Zexu, a very capable and ambitious Chinese government official, they argued that the opium trade was a moral issue, and an “evil” that had to be eliminated by any means possible. If they could not suppress the trade of opium and addiction to it, the Chinese empire would have no peasants to work the land, no townsfolk to pay taxes, no students to study, and no soldiers to fight. They argued that instead of targeting opium users, they should stop and punish the “pushers” who imported and sold the drug in China. In the end, Lin Zexu’s side won the argument. In 1839, he arrived in Guangzhou (Canton) to supervise the ban on the opium trade and to crack down on its use. He attacked the opium trade on several levels. For example, he wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria questioning Britain’s political support for the trade and the morality of pushing drugs. More importantly, he made rapid progress in enforcing the 1813 ban by arresting over 1,600 Chinese dealers and seizing and destroying tens of thousands of opium pipes. He also demanded that foreign companies (British companies, in particular) turn over their supplies of opium in exchange for tea. When the British refused to do so, Lin stopped all foreign trade and quarantined the area to which these foreign merchants were confined. After six weeks, the foreign merchants gave in to Lin’s demands and turned over 2.6 million pounds of opium (over 20,000 chests). Lin’s troops also seized and destroyed the opium that was being held on British ships—the British superintendent claimed these ships were in international waters, but Lin claimed they were anchored in and around Chinese islands. Lin then hired 500 Chinese men to destroy the opium by mixing it with lime and salt and dumping it into the bay. Finally, he pressured the Portuguese, who had a colony in nearby Macao, to expel the uncooperative British, forcing them to move to the island of Hong Kong. Taken together, these actions raised the tensions that led to the outbreak of the first Opium War. For the British, Lin’s destruction of the opium was an affront to British dignity and their concepts of trade. Many British merchants, smugglers, and the British East India Company had argued for years that China was out of touch with “civilized” nations, which practised free trade and maintained “normal” international relations through consular officials and treaties. More to the point, British representatives in Guangzhou requested that merchants turn over their opium to Lin, guaranteeing that the British government would compensate them for their losses. The idea was that in the short term, this would prevent a major conflict, and that it would keep the merchants and ship captains safe while reopening the extremely profitable China trade in other goods. The huge opium liability (the opium was worth millions of pounds sterling), and increasingly shrill demands from merchants in China, India, and London when they discovered their profits were destroyed, gave politicians in Great Britain the excuse they were looking for to act more forcefully to expand British imperial interests in China. War broke out in November 1839 when Chinese warships clashed with British merchantmen. In June 1840, 16 British warships and merchantmen—many leased from the primary British opium producer, Jardine Matheson & Co.—arrived at Guangzhou. Over the next two years, the British forces bombarded forts, fought battles, seized cities, and attempted negotiations. A preliminary settlement called for China to cede Hong Kong to the British Empire, pay an indemnity, and grant Britain full diplomatic relations. It also led to the Qing government sending Lin Zexu into exile. Chinese troops, using antiquated guns and cannons, and with limited naval ships, were largely ineffective against the British. Dozens of Chinese officers committed suicide when they could not repel the British marines, steamships, and merchantmen. The War’s Aftermath The first Opium War ended in 1842, when Chinese officials signed, at gunpoint, the Treaty of Nanjing. The treaty provided extraordinary benefits to the British, including: an excellent deep-water port at Hong Kong; a huge indemnity (compensation) to be paid to the British government and merchants; five new Chinese treaty ports at Guangzhou (Canton), Shanghai, Xiamen (Amoy), Ningbo, and Fuzhou, where British merchants and their families could reside; extraterritoriality for British citizens residing in these treaty ports, meaning that they were subject to British, not Chinese, laws; and a “most favoured nation” clause that any rights gained by other foreign countries would automatically apply to Great Britain as well. For China, the Treaty of Nanjing provided no benefits. In fact, Chinese imports of opium rose to a peak of 87,000 chests in 1879 (see Figure 1). After that, imports of opium declined, and then ended during the First World War, as opium production within China outgrew foreign production. However, other trade did not expand as much as foreign merchants had hoped, and they continued to blame the Chinese government for this. Among Chinese officials, the aftermath of the war led to a bitter political struggle between two factions: a peace faction, which was roughly aligned with the ‘users’ faction in the opium trade debate; and a ‘war’ faction, which was roughly aligned with the ‘pushers’ faction in that debate. The peace faction was in nominal control.  In addition, the Treaty of Nanjing ended the Canton System that had been in place since the 17th century. This was followed in 1844 by a system of unequal treaties between China and western powers. Through the most favoured nation clauses, these treaties allowed westerners to build churches and spread Christianity in the treaty ports. Western imperialism and free trade had its first great victory in China with this war and its resulting treaties. When the Chinese emperor died in 1850, his successor dismissed the peace faction in favour of those who had supported Lin Zexu. The new emperor tried to bring Lin back from exile, but Lin died along the way. The Chinese court kept finding excuses not to accept foreign diplomats at the capital city of Beijing, and its compliance with the treaties fell far short of western countries’ expectations. Second Opium War (1856–1860) In 1856, a second Opium War broke out and continued until 1860, when the British and French captured Beijing and forced on China a new round of unequal treaties, indemnities, and the opening of 11 more treaty ports (see Map 3). This also led to increased Christian missionary work and legalization of the opium trade. Even though new ports were opened to British merchants after the first Opium War, the Chinese dragged their feet on implementing the agreements, and legal trade with China remained limited. British merchants pressed their government to do more, but the government’s hands were tied because the Chinese government in the capital city of Beijing restricted who it met with. In October 1856, Chinese authorities arrested the Chinese crew of a ship operated by the British. The British used this as an opportunity to pressure China militarily to open itself up even further to British merchants and trade. France, using the execution in China of a French Christian missionary as an excuse, joined the British in the fight. Joint French-British forces captured Guangzhou before moving north to the city of Tianjin (also referred to as Tientsin). In 1858, the Chinese agreed—on paper—to a series of western demands contained in documents like the Treaty of Tientsin. But then they refused to ratify the treaties, which led to further hostilities. In 1860, British and French troops landed near Beijing and fought their way into the city. Negotiations quickly broke down and the British High Commissioner to China ordered the troops to loot and destroy the Imperial Summer Palace, a complex and garden where Qing Dynasty emperors had traditionally handled the country’s official matters. Shortly after that, the Chinese emperor fled to Manchuria in northeast China. His brother negotiated the Convention of Beijing, which, in addition to ratifying the Treaty of Tientsin, added indemnities and ceded to Britain the Kowloon Peninsula across the strait from Hong Kong. The war ended with a greatly weakened Qing Dynasty that was now confronted with the need to rethink its relations with the outside world and to modernize its military, political, and economic structures. Thinking About the Opium War In 1839, the British imposed on China their version of free trade and insisted on the legal right of their citizens (that is, British citizens) to do what they wanted, wherever they wanted. Chinese critics point out that while the British made lofty arguments about the ‘principle’ of free trade and individual rights, they were in fact pushing a product (opium) that was illegal in their own country. There are different viewpoints on what was the main underlying factor in Britain’s involvement in the Opium Wars. Some in the west claim that the Opium Wars were about upholding the principle of free trade. Others, however, say that Great Britain was acting more in the interest of protecting its international reputation while it was facing challenges in other parts of the world, such as the Near East, India, and Latin America. Some American historians have argued that these conflicts were not so much about opium as they were about western powers’ desire to expand commercial relations more broadly and to do away with the Canton trading system. Finally, some western historians say the war was fought at least partly to keep China’s balance of trade in a deficit, and that opium was an effective way to do that, even though it had very negative impacts on Chinese society. It is important to point out that not everyone in Britain supported the opium trade in China. In fact, members of the British public and media, as well as the American public and media, expressed outrage over their countries’ support for the opium trade.2 From China’s historical perspective, the first Opium War was the beginning of the end of late Imperial China, a powerful dynastic system and advanced civilization that had lasted thousands of years. The war was also the first salvo in what is now referred to in China as the “century of humiliation.” This humiliation took many forms. China’s defeat in both wars was a sign that the Chinese state’s legitimacy and ability to project power were weakening. The Opium Wars further contributed to this weakening. The unequal treaties that western powers imposed on China undermined the ways China had conducted relations with other countries and its trade in tea. The continuation of the opium trade, moreover, added to the cost to China in both silver and in the serious social consequences of opium addiction. Furthermore, the many rebellions that broke out within China after the first Opium War made it increasingly difficult for the Chinese government to pay its tax and huge indemnity obligations. Present-day Chinese historians see the Opium Wars as a wars of aggression that led to the hard lesson that “if you are ‘backward,’ you will take a beating.” These lessons shaped the rationale for the Chinese Revolution against imperialism and feudalism that emerged, and then succeeded, decades later. _________________________ | |||

|

Irksome Whirling Dervish |

Yes there is. Last week in Bloomfield, CT a teenager died at school from Fentanyl laced MJ. He was given multiple doses of Narcan however he could not be recovered. | |||

|

| Member |

^^^^^^^^^^ I would say upscale rehab facilites. The ones treating the Medicaid/Medicare population are not nearly as profitable. 90 days is the gold standard these days. Rehabs that take cash only do very well. | |||

|

| Fire begets Fire |

It’s flipping poison I tell y’all "Pacifism is a shifty doctrine under which a man accepts the benefits of the social group without being willing to pay - and claims a halo for his dishonesty." ~Robert A. Heinlein | |||

|

| Member |

Go to the link to see what is really happening with drugs in San Fransico. Videos there that I don't know how to post. It gives a realistic view of what life is like for an addict. Ben says 95% of people have switched from heroin to fentanyl, and that some dealers aren't even selling it any more He says the price came down from $200 to $60 a day over the last two years https://threadreaderapp.com/th...130669875253250.html _________________________ | |||

|

| A day late, and a dollar short  |

That's some scary shit to hear, glad I don't smoke dope! ____________________________ NRA Life Member, MGO Annual Member | |||

|

| Ignored facts still exist |

Well, there's the supply side, which is the topic here, and then there's reducing the demand at the end user level. Oregon decriminalized hard drugs recently. So, fentanyl is now "decriminalized" at the user level. The thought was resources would go toward drug treatment, social work, etc. instead of law enforcement / jails/ courts. Honestly it doesn't seem to be going according to plan. The homeless camps are still full of drugs and now no arrests can be made at the user level. Actually, it's not just the homeless camps, it's elsewhere too. ...and .... Deaths are still rising in the state at a sharp rate. So, decriminalization at the user level seems to not be the answer, at least the way Oregon's Measure 110 did it. Of course, it's still early. Only passed less than 2 years ago. . | |||

|

| Lawyers, Guns and Money |

Move over fentanyl: here comes xylazine By Thomas Lifson I had picked up from the media that a drug called “trank” was showing up and killing people the way that fentanyl does: by being mixed in with other street drugs that are purchased by primarily young people who don’t know any better. But thanks to the intrepid crime reporters at CWB Chicago , now I understand the extent to which the problem has spread and why it is even worse than fentanyl: A tranquilizer used to sedate horses, cattle, and other animals is making its way into the illicit drug market, secretly added to heroin and cocaine by dealers trying to stretch their profits, authorities say. But unlike another powerful drug that dealers use to cut narcotics, fentanyl, xylazine is not an opioid, and its effects cannot be reversed by administering Narcan. Cook County had never recorded a xylazine-related death until 2018 when it had one case. Last year, there were 162, tweeted Luis Agostini, the Drug Enforcement Administration’s public information officer in Chicago. Fentanyl is being mixed with xylazine to cheaply extend the impact of the other illegal drugs being sold. Because Narcan is useless against it, there are more deaths. Nearly a quarter of the fentanyl seized by the DEA last year contained xylazine, CBS reported recently. “Data shows that just about every xylazine-related death reported in Cook County also involves fentanyl. Purchasing drugs illegally – on the street or online without prescription – is a dangerous gamble,” Agostini tweeted last summer. The problem is accelerating: Around this time last year, Cook County had confirmed 41 xylazine-related deaths, Cook County Chief Medical Examiner Ponni Arunkumar told NBC’s affiliate in Terre Haute at the time. That number has more than doubled to 84 after outstanding toxicology tests came back, according to the medical examiner’s online data portal. We know that the gangs behind this drug trade are ruthless, and care not in the least about the toll their business exacts in lost lives. I would note that Singapore, which strictly applies to death penalty for dealing drugs (even marijuana), has no real drug problem. That almost always strikes Americans as ridiculously severe and even inhumane. But is it more humane to allow this trade to kill scores of people a year in just one city? Just think about that for a while. https://www.americanthinker.co..._comes_xylazine.html "Some things are apparent. Where government moves in, community retreats, civil society disintegrates and our ability to control our own destiny atrophies. The result is: families under siege; war in the streets; unapologetic expropriation of property; the precipitous decline of the rule of law; the rapid rise of corruption; the loss of civility and the triumph of deceit. The result is a debased, debauched culture which finds moral depravity entertaining and virtue contemptible." -- Justice Janice Rogers Brown "The United States government is the largest criminal enterprise on earth." -rduckwor | |||

|

| Member |

I'm curious as to why all these 65 year olds that you know were taking it. _____________________ Be careful what you tolerate. You are teaching people how to treat you. | |||

|

Raptorman |

I just got over a kidney stone. They gave me morphine sulphate to take home with me along with a couple dozen percosets. I was in a pain filled fog. The second doctor gave me some Trazodone, which is not narcotic and a newer NSAID which worked FLAWLESSLY. No pain, no fog. I can't STAND they way this shit makes me feel and I can't understand why anyone else would enjoy it. ____________________________ Eeewwww, don't touch it! Here, poke at it with this stick. | |||

|

| Member |

It is biology and environment. I have yet to meet a heroin addict or alcoholic who chose to be that way. Clearly your biology is different. BTW sometimes NSAIDS work a lot better than narcotics. In my case 800mg Motrin did the trick. Hydrocodone never really worked for me. | |||

|

Fighting the good fight |

Trazodone is an antidepressant. They gave you that for pain relief? Or do you mean Tramadol? That is an opiate and a narcotic, but it has a lower risk of abuse than most of the more potent opiate pain killers, and is generally the lowest-level opiate pain killer prescribed. I have funky side effects from most opiates, including morphine. But not from Tramadol. That's what I requested when recovering from my knee surgery. They started out stating they were going to prescribe me hydro-this and oxy-that, and I declined and stated that I would take Tramadol for a few days until it could be managed with just NSAIDs. I've declined Rx painkillers before for broken bones, and instead took 1000mg of NSAIDs at a time. | |||

|

| Member |

Tramadol is a HUGE problem in Africa where it is dirt cheap. It is abused so much that it has gotten into the soil. When they were harvesting vegetables, they found the vegetables had remarkable pain relieving qualities. In fact the vegetables were infused with Tramadol.Have a look: reality death is rolling towards you.” The man says he has had nearly a dozen tramadol-induced seizures. In another neighbourhood, a motley group of motorcycle taxi drivers all have stories to tell. About how some of their colleagues crashed their bikes, not even noticing they were hurt because they didn’t feel any pain. About how they can go a whole day without eating, or how they mix tramadol with energy drinks, instant coffee or sodabi, a strong locally distilled spirit, to get an extra kick. One of the men is obsessively polishing his bike with a cloth and a toothbrush. It is already sparkling in the sun but he carries on. Those who take tramadol have an excess of nervous energy and cannot sit still. A sex worker who has been taking tramadol daily for two years says it helps her cater to more customers and walk the streets all night. The 225mg tablet she takes every day doesn’t have the same effect it used to, but she doesn’t want to increase her dosage. She has seen what it does to others. Some lose control, they get nervous and into fights, while some fall asleep while having sex with a customer. She can tell when her customers are high on the drug, too: “They are more horny and rough-rough.” Ayao waiting outside a bar while his friend goes inside to buy alcohol Ayao waiting outside a bar while his friend goes inside to buy alcohol (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) The pills these non-medical users take are typically between 120 and 250mg, though some speak of strengths of up to 500mg. They buy single blisters from medicine peddlers, but also from market women, dealers and roadside tea and coffee vendors for between 250 and 500 francs (35–70 pence), depending on the dosage. The minimum wage in Togo is 35,000 francs (£50) per month. A 36-year-old motorcycle taxi driver recounts that he once managed to quit for three months. His body hurt all over. “It was a mental battle that I lost,” he says. Other withdrawal symptoms include profuse sweating, breathing difficulties, anxiety, stomach cramps and depression. Everyone around him takes tramadol. Many want to stop. They just don’t know where to find help. Around the region, the few formal options that do exist for drug addicts are often embedded in psychiatric hospitals. But the stigma around checking into such an institution is strong. People say they might be addicts, but they are not fou, or “mad”. *** In Togo, and most other countries, tramadol is officially a prescription-only drug. While there might be pharmacies that will sell it without one, in sub-Saharan Africa a large proportion of people buy their medicines in the informal sector. Often neither vendor nor customer really understands what’s being bought and sold, especially given that pills frequently don’t contain what is stated on the packet. This is because the bulk of tramadol used for non-medical purposes is not diverted from legitimate pharmaceutical sources. Rather, it’s made up of unlicensed, counterfeit or substandard pills manufactured primarily in India and China, which are then trafficked to north and west Africa. “We have seen an increase in seizures of tramadol in various countries, especially those with sea borders where tramadol usually enters the region – Benin, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria,” says Jeffery Bawa, drug control and crime prevention officer for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Sahel Programme. In 2018 alone Nigeria seized 6.4 billion tramadol tablets. From the ports of west Africa the cargo is then dispersed throughout the region. According to the 2018 UNODC world drug report, north, central and west Africa accounted for 87 per cent of pharmaceutical opioids seized worldwide, a development due almost entirely to tramadol trafficking. A zémidjan (motorcycle taxi) rider in Lomé obsessively cleaning his bike (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) In Togo, while there have been big seizures of several tonnes at the port in the past, nothing on that scale has been recorded in the past two years. Raids on market and street vendors selling illicit medication have, however, increased, pushing tramadol underground. “Now that we have started to strike, to repress, to seize the illicit products the bonnes dames [market women] sell, it’s begun to enter the clandestine,” says Mawouéna Bohm, deputy permanent secretary of the National Anti-Drug Committee. “That’s to say, the bonnes dames sell it to clients they know very well, and who also come with secret codes.” Anecdotes from the street support this. “Tramadol is trouble,” says one medicine peddler at the Grand Marché. “If the police find you with it, it is a problem.” Everyone has become more secretive. Even Ayao says he never buys more than one or two pills at a time. “It would not be good if the police catch me with it,” he says. As a result of the crackdown, prices have risen sharply in the past few months. Whereas a 120mg capsule cost 50 francs before, it now costs up to 300 francs. The 225 or 250mg pills sell for up to 500 francs. Neighbouring Ghana has also taken steps to combat the abuse of tramadol on its streets, after the problem intensified in 2017. On a national level tramadol is now a controlled substance. Alongside an increase in law enforcement, the country has held nationwide pharmaceutical crime training so that “police would treat counterfeit drugs with the same urgency as they do arms,” explains Olivia Boateng, head of the Tobacco and Substances of Abuse Department at Ghana’s Food and Drugs Authority. Through advocacy and education efforts, the Ghanaian authorities are also teaching people that this is a substance with health implications. “The feedback we are getting is that the abuse of tramadol has gone down considerably,” says Boateng. A market in the Lomé neighbourhood of Atikoumé (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) But corruption, porous borders and the free movement of people create a challenge across the west African region. According to Boateng, the majority of the drug peddlers arrested in the Ghanaian crackdown were from Niger, Nigeria and Togo. “They carried the tramadol across unapproved routes on motorbikes. We also had a truck impounded, where tramadol was concealed in loads of other products that were not medicine.” Facing similar challenges, in recent years Egypt has put the painkiller under strict national control. But seizures of unlicensed tramadol have remained significant. In 2017 more than 60 per cent of those treated in a state-run addiction facility still named tramadol as their main substance of abuse. So in response, Egypt called for tramadol to be internationally controlled. However, in March 2019 the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs declined to add tramadol to its list of scheduled substances. Its concern was that international controls might make access harder for those in low-income countries who genuinely need the painkillers. Grace (right) and her friend Ismael visiting Selasse, who has sickle-cell disease, and her mother. Selasse has difficulty speaking and is partially paralysed as a result of a stroke, which is one of the risks of the disease (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) Grace Kudzu looks at her watch. It is time for her injection. She grabs a light brown vinyl purse and steps out of her parents’ large house, crossing the spacious veranda and heading through the garden gate onto a sandy road in one of Lomé’s quiet neighbourhoods. Her walk is controlled and slow – she almost seems to economise her movements. Two streets on, she enters a courtyard, where she is greeted by Kodjo Touré*. The nurse, dressed in a white coat, runs a little neighbourhood clinic from his house. Grace has sickle-cell disease, a genetic disorder of the red blood cells. While normally these cells are shaped like doughnuts, making them flexible so they can squeeze through even the smallest blood vessels, with sickle-cell they are shaped like a crescent moon, making them rigid. They get stuck in capillaries, blocking the blood flow to parts of the body. This can cause damage to bones, muscles and organs, and episodes of excruciating pain known as vaso-occlusive crises. The disease is most common in sub-Saharan Africa, India, Saudi Arabia and Mediterranean countries, and in Togo an estimated 4 per cent of the population suffer from it. “It is a sickness I would not wish upon my worst enemy,” Grace says. For five days now she has been having one of her painful episodes. Over the past five years, the vaso-occlusive crises have started to come more regularly. On average she has two of them a month, each lasting a week or more. I call it my little monster that wakes up when it wants to Grace on living with sickle-cell disease “If the pain wants to be kind to me, it comes slowly, but most of the time it just suddenly pops up in my body,” Grace says. The day before, a combination of fever and pain made her vomit. “I had to tie a cloth around my chest to be able to breathe. The pain felt like something was squashing my lungs.” Only regular injections of painkillers bring Grace some relief. She has come to Touré’s clinic so often that he no longer charges her. And anyway, she carries everything she needs in her purse. In it are syringes, disinfectant solution, cotton wool, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory ketoprofen, and five ampoules each containing 100mg of tramadol. The problem is that for Grace, tramadol often isn’t enough to ease her pain. She has to make do because in Togo, stronger pain medications, like morphine, are rarely available. Touré breaks open one of the tramadol ampoules, draws the liquid into a syringe and injects it into Grace’s arm. For just an instant her self-control cracks. She looks exhausted. Grace and her friend Ismael bringing a box of provisions to the home of a young woman with sickle-cell disease. Grace has the disease herself, and volunteers full-time in care and counselling (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) Later, Grace is sitting next to a young woman lying on a metal-framed hospital bed at the National Sickle Cell Research and Care Centre. Seventeen-year-old Jennifer, like Grace, also suffers from sickle-cell disease. She has been in the throes of a vaso-occlusive crisis for days. In general, such crises are triggered by sudden temperature change, dehydration, strenuous physical exercise and a lack of oxygen. “She woke up at night crying,” says Thierry, Jennifer’s father. At the centre the teenager was put on a drip containing tramadol together with other medications. It took two nurses seven painful attempts to find a vein that did not collapse as soon as the cannula was inserted. Finally one of them succeeded, finding a vein at the base of Jennifer’s thumb. By the time the fluid started flowing, Jennifer was whimpering in pain and frustration, tears rolling down her cheeks. Grace bends over Jennifer, speaking to her in a soothing voice. “I call it my little monster that wakes up when it wants to,” she says to the younger girl. “You have to accept your condition. You have to learn to live with it.” Grace spends most of her time advancing the cause of her “sickle-cell brothers and sisters”. She is the founder of the association Drépano Solidaires (United Against Sickle Cell) and is trying to set up an NGO to provide psychosocial support to people with the disease. She also finds the time to volunteer at the centre, preparing files for the doctors and counselling patients and their relatives. She comes every day, even when her own pain is hard to bear, as it was when she had to tie the cloth around her chest to be able to breathe. In pain and overdue for a dose, Grace Kudzu, 35, injects herself with 100mg of tramadol in the front seat of a friend’s car in Lomé (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) On a scale of 0 to 5, her pain was at 4.3, she says. At that point tramadol is just not enough. The painkiller is ranked at step 2 of the WHO pain ladder, a guideline for the use of drugs to manage pain. “Sometimes when you are having the pain like this,” Grace says, “they can inject you those things, but it will not ease it.” According to the ladder, if weak opioids such as tramadol or codeine become insufficient, they should be replaced by a strong step 3 opioid such as morphine, fentanyl or oxycodone. But these are not readily available in Togo. “You see people, they are suffering, suffering, and all that we have is tramadol and ketoprofen to ease the pain,” says Grace. “It would be a good thing if we can go to level 3.” “When one prescribes [morphine], you really have to do a tour of all the pharmacies in Lomé and have the luck to find it at one,” says Hèzouwè Magnang, a haematologist and the director of the sickle-cell centre. “One makes do with analgesics of step 2.” He says it’s troubling when “you reach the end of your means” and a patient is still in pain. The reasons for the shortage of step 3 painkillers are numerous and they compound each other. Jennifer, 17, who has sickle-cell disease, with Dr Hèzouwè Magnang. She is having a consultation for a vaso-occlusive crisis – an episode of severe pain – at the National Sickle Cell Research and Care Centre in Lomé (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) Unlike tramadol, step 3 substances such as morphine are internationally scheduled, and countries must put forward annual estimates of their needs. “This is often a problem,” explains Thomas Pietschmann, a drug research expert from the UNODC based in Vienna, Austria. “Although it is a simple calculation – how many sick there are and therefore how much pain medication is needed – many governments do not want to taint their image,” Pietschmann says. “So they do not declare the actual amount of controlled substances needed by their population, leading to a catastrophic shortage of controlled opiates such as morphine, especially in many African and Asian countries.” The World Health Organization estimates that 5.5 billion people – around 83 per cent of the world’s population – live in countries with low to non-existent access to controlled medicines and inadequate access to treatment for moderate to severe pain. 5.5 billion People living in countries with little to no access to moderate/severe pain treatment The 2019 estimates put forward for Togo, with its population of approximately 8 million, reflect what Pietschmann says. A total of six scheduled substances are on its list, with only three being of any significant amount: 16g of fentanyl, 2,000g of morphine and 4,000g of pethidine. By comparison, in Switzerland, a country with a similar population, the numbers lie at 22,000g, 1.45 million g and 61,000g respectively, and its lists includes more than 30 substances in total. When strong opioid painkillers do arrive in lower-income countries, they can usually only be prescribed and administered by doctors. And there are not enough of them. In Togo, there is only one doctor for every 20,500 people (the Swiss figure is one for 236). Beyond this, there is a capacity development problem in west Africa. “The number of physicians trained in palliative care management in Ghana is woefully inadequate,” says Maria-Goretti Ane Loglo, a Ghanaian lawyer and regional consultant to the International Drug Policy Consortium, who advises west African governments on drug policy. “The laws are strict, and doctors are afraid to prescribe morphine in case something goes wrong and they have to face the consequences.” Nurses struggle to find a viable vein for an intravenous drip to treat Jennifer’s vaso-occlusive crisis (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) Magnang concurs. Strong opioid painkillers can have severe side effects, and in his opinion it’s not worth the risk of administering morphine if one doesn’t have the capability to deal with them. In low-income countries there is also a degree of “opiophobia”, perhaps as a result of the lack of expertise, and doctors avoid morphine for fear of patients becoming addicted. Finally, because morphine is internationally scheduled, ordering and selling it involves paperwork and bureaucracy for pharmacies. “In Ghana, according to a number of pharmacy shops we spoke to, the turnover of morphine is less than 2 per cent,” says Ane Loglo. “It’s not worth the trouble. I bring in morphine, it is not prescribed, it stays in the shelves and it expires.” Magnang worries about what would happen if tramadol fell under the same regulatory framework. According to him there are already too few step 2 choices. “If one hardens the regulations such that we don’t have access to tramadol, I think it would reduce the scope of doctors’ options,” he says. Yem-bla Pharmacy in Lomé (Nyani Quarmyne/Panos for Mosaic) But if tramadol were internationally scheduled, would it fix the abuse problem in the region? Olivia Boateng from Ghana’s Food and Drugs Authority thinks it would help. “If we sit in Ghana and do our own laws in isolation and Nigeria does not do the same thing, we will have a spillover,” she says. “But if it were internationally scheduled, it would cut across and bring about a safe, legitimate supply chain. We have had [scheduled] morphine over the years, but have not had this sort of global abuse we have with tramadol.” While a worldwide law isn’t on the horizon, interregional cooperation on tramadol is growing. Last year, India introduced measures to control the drug under its narcotics law, giving its authorities the power to deal with illicit manufacturing and smuggling. And in May, the UNODC and the International Narcotics Control Board organised a trilateral meeting between India, Ghana and Nigeria to look at how to counter tramadol trafficking. However, Ane Loglo is less sanguine about international control. In her view, advocacy, education and interagency cooperation – rather than repression, which pushes the drug underground – can be effective. But where an international perspective is needed, she says, is in recognising that tramadol is just one small part of the region’s much bigger problem of counterfeit medication, much of which is substandard. Fake pharmaceuticals in Africa account for up to 30 per cent of the market. The worldwide market is estimated to be worth up to US$200bn. Even if tramadol were controlled internationally and the flow of it were stemmed, as long as the counterfeit market continues to flourish, something else will simply take tramadol’s place. Boateng also worries about this, especially if the underlying issue of addiction in general is not addressed. “We will have another molecule, chemical or product on our hands very soon. If we don’t tackle the addiction problem, we will always be doing this firefighting.” Recommended Louvre museum removes name of Sackler family linked to opioid crisis Billionaire drug firm boss guilty of bribing doctors to push fentanyl Mother’s search for truth about US opioid crisis reaches White House Restaurant apologises for Instagram post joking about opioid addiction FDA approves opioid painkiller up to 10 times stronger than fentanyl Indeed, back in Lomé, Ayao is hanging out with a friend in his neighbourhood. They’re talking about a little white pill that’s new on the streets, nicknamed écouteurs (headphones) after the motif on its face. They don’t know exactly what it is, only that it is much stronger than tramadol, and cheaper, too, now that the price of tramadol has gone up. But neither seems keen to dabble with it. They recount stories they’ve heard about its mind-muddling effects. In fact, Ayao says he already regrets the impact tramadol has had on his life. He feels left out when his former classmates talk about things that are happening at school. Perhaps if someone had told him about the dangers of tramadol before he started taking it, things would look different today. While it may be too late for Ayao, NGOs and civil rights groups such as ANCE-Togo have extended their school- and community-based programmes on alcohol and tobacco to include tramadol, hoping to prevent kids from experimenting with it in the first place. There are also measures being put in place to address the lack of strong painkillers for people like Grace. The Ministry of Health has an action plan for integrating palliative care into all levels of the Togolese health system. This has already included sending a small cohort of health workers to Uganda to learn from the pioneering approach to sustainable palliative care there, one aspect of which is that nurses and clinical officers can prescribe oral liquid morphine. But these measures are likely to take a long time to show any real effect. Support free-thinking journalism and attend Independent events In the meantime, Grace remains unwilling to give in to her pain. She’s promised herself that she will continue to transform her suffering into strength, and is working towards going to the US to study public health. That way, she says, she can participate in the conception and implementation of policies that will help people with sickle-cell in her own country. “I want to live a good life,” she says, “and not regret anything.” * Some names have been changed. LINK: https://www.independent.co.uk/...africa-drugs-togo-a9 | |||

|

Step by step walk the thousand mile road |

Strange... I proposed a similar idea in this Thread back in 2017.

The responses: "That's so far off base it's laughable, pitiful and just right out of the stuff that makes Infowars so seedy and disgusting." "I think your over thinking the situation." So I'm glad someone else has cottoned onto China's REAL plan. China wants America GONE as a superpower. China is supplying the Mexican Drug Cartels (MDCs) with the precursors for fentanyl, so its produced in Mexico, and not in China. China knows these drugs are going to America. Why not do this, plus make a MST of money selling the precursors to a cutout (MDCs), thereby creating plausible deniability? Nice is overrated "It's every freedom-loving individual's duty to lie to the government." Airsoftguy, June 29, 2018 | |||

|

Fighting the good fight |

Any opiate can be abused. But Tramadol is a lower risk, since it is significantly less powerful than other opiate drugs, and is metabolized differently from many opiate drugs. Do you have a reference for this claim of "Tramadol veggies"? It isn't mentioned in the article you tried to post... And ZSMICHAEL, this may sound harsh, but I truly wish you would spend a bit more time and effort copying, pasting, and editing your news articles. You're a very prolific poster, with many of your posts and threads being copied news articles that oftentimes seem genuinely interesting and educational, but this habit you have of just highlighting everything on a news webpage and then dumping it all into a forum post renders your articles unreadable, with the actual text of the article muddled between fragmented sentences, nonsensical image caption inserts, janky formatting, broken links, etc. A bit more care spent on formatting and editing would likely result in more members reading and considering your article posts. | |||

|

| Member |

Glad you read the article. You may note it was edited. The original was published some time ago. The reference to veggies must have been in the original article. I do my best at editing which takes considerable time and effort. On the trail of a drug in plants Nature volume 513, page463 (2014)Cite this article The painkiller tramadol is not made naturally by plants despite last year's surprising finding that the drug was present in the roots of a Cameroonian plant (Nauclea latifolia). LINK: https://www.nature.com/articles/513463b | |||

|

thin skin can't win |

When it makes it into Cheerios, or legitimate domestic RX drugs, I'll care more. You only have integrity once. - imprezaguy02 | |||

|

Raptorman |

Generic Toradol, Ketorolac 10mg. I can't keep up with all these names. Worked amazing. No pain, no stupid fog. Did NOTHING for my arthritis, but that's another show. ____________________________ Eeewwww, don't touch it! Here, poke at it with this stick. | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata | Page 1 2 3 4 5 |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

© SIGforum 2025