SIGforum.com  Main Page

Main Page  The Lounge

The Lounge  US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

Main Page

Main Page  The Lounge

The Lounge  US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignitionPage 1 2

Go  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| Lead slingin' Parrot Head |

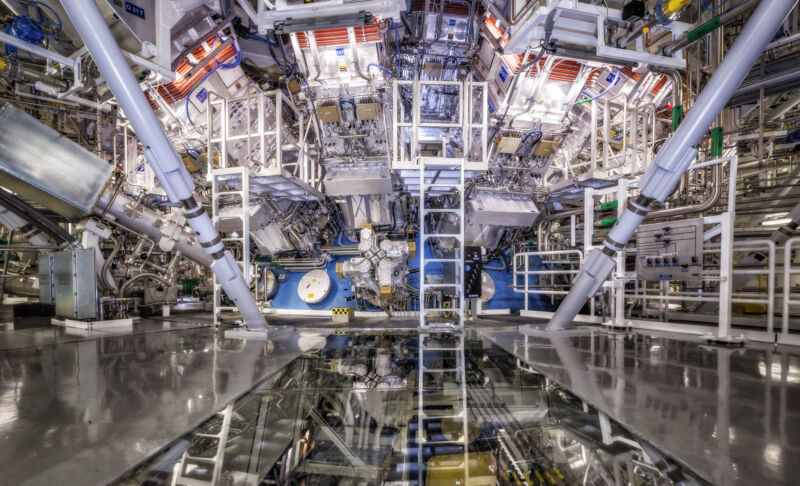

The legacy media has been crowing about this announcement for the last couple days as though the Biden regime just single-handedly conquered global warming by merely being in office when this break through occurred... even though there remain significant technical challenges that probably won't be overcome for a couple decades or more. Having said that, this is a significant milestone worth noting, and getting excited about. This achievement does make me wonder if it wouldn't be better to back away from this frenzied push to adopt solar/ wind/ EVs and instead reserve our national capital to adopt nuclear as an interim energy source, until fusion technology has matured to a point for mass commercialization. [Note: multiple hyperlinks found at linked website article.] =================== What enabled the big boost in fusion energy announced this week? Two megajoules of laser yielded three megajoules of fusion energy by John Timmer - Dec 13, 2022 12:15pm MST  Where the action happens inside the National Ignition Facility. Damien Jemison/LLNL On Tuesday, the US Department of Energy (DOE) confirmed information that had leaked out earlier this week: its National Ignition Facility had reached a new milestone, releasing significantly more fusion energy than was supplied by the lasers that triggered the fusion. "Monday, December 5, 2022 was an important day in science," said Jill Hruby, head of the National Nuclear Security Administration. "Reaching ignition in a controlled fusion experiment is an achievement that has come after more than 60 years of global research, development, engineering, and experimentation." In terms of specifics, the lasers of the National Ignition Facility deposited 2.05 megajoules into their target in that experiment. Measurements of the energy released afterward indicate that the resulting fusion reactions set loose 3.15 megajoules, a factor of roughly 1.5. That's the highest output-to-input ratio yet achieved in a fusion experiment. Before we get to visions of fusion power plants dotting the landscape, however, there's the uncomfortable fact that producing the 2 megajoules of laser power that started the fusion reaction took about 300 megajoules of grid power, so the overall process is nowhere near the break-even point. So, while this was a real sign of progress in getting this form of fusion to work, we're still left with major questions about whether laser-driven fusion can be optimized enough to be useful. At least one DOE employee suggested that separating it from its nuclear-testing-focused roots may be needed to do so. Check ignition During today's announcement, the DOE's Marv Adams described the National Ignition Facility's process for using lasers to trigger fusion. It involves placing a small target sphere containing hydrogen isotopes inside a metal cylinder, and then zapping the cylinder with lasers. "192 laser beams entered from the two ends of the cylinder and struck the inner wall, Adams said. "They didn't strike the capsule, they struck the inner wall of this cylinder and deposited energy. And that happened in less time than it takes light to move 10 feet. So it's kind of fast." The cylinder released much of the energy it received in the form of X-rays, which compress the small hydrogen target—another speaker compared the compression to smashing a basketball down to the size of a pea. The intense heat and compression set off fusion among the hydrogen isotopes, releasing energetic photons and neutrons. These carry much of the excess energy produced during the reactions. The Department of Energy built the National Ignition Facility partly because hydrogen fusion is at the heart of many of its nuclear weapons and because fusion is a potential power source that produces far less—and far less dangerous—nuclear waste than nuclear fission. The press conference makes clear that, over the past several years, the team operating the National Ignition Facility has gradually improved yields through an iterative process. They have several knobs they can turn—different ways to distribute the lasers' power across individual beams, different ways of managing small defects on the target, etc. These could alter not only the amount of fusion that starts in the target, but how its energy spreads into the surrounding hydrogen isotopes. "That plasma wants to immediately lose its energy—it wants to blow apart, it wants to radiate, it's looking for ways to cool down," said Livermore Labs' Mark Herrmann. "But the fusion reactions are depositing heat in that plasma, causing it to heat up, so there's a race between heating and cooling. And if the plasma gets a little bit hotter, the fusion reaction rate goes up, creating even more fusion, which gets even more heating. And, so the question is, can we win the race. And for many, many decades, we lost the race. We got more cooling out than we got the heating up." But all those lost races led to better models of the reaction conditions, including recent ones refined by machine-learning studies of past tests, as well as improved manufacturing of targets. And that led to a tweak of the distribution of laser energy that led to a more symmetric target compression in the recent experiment. And that, apparently, made enough of a difference to produce this unusually high yield, even though Annie Kritcher, who leads the experimental design team, indicated that the pre-tweak experiments only produced about 1.2 megajoules of output energy. The DOE indicated that the conditions haven't been replicated yet, but it brought in a panel of outside experts to review its measurements before making this announcement. (Or at least not replicated in the real world. "I had vivid dreams of all possible outcomes from the shot," Kritcher said. "This always happens before a shot from, like, complete success to utter failure.") About that energy yield As we noted above, the 3 MJ released in this experiment is a big step up from the amount of energy deposited in the target by the National Ignition Facility's lasers. But it's an enormous step down from the 300 MJ or so of grid power that was needed to get the lasers to fire in the first place. But many speakers emphasized that the facility was built with once-state-of-the-art technology that's now over 30 years old. And, given its purpose of testing conditions for nuclear weapons, keeping power use low wasn't one of the design goals. "The laser wasn't designed to be efficient," said Herrmann, "the laser was designed to give us as much juice as possible to make these incredible conditions happen in the laboratory." Tammy Ma leads the DOE's Inertial Fusion Energy Institutional Initiative, which is designed to explore its possible use for electricity generation. She estimated that simply switching to current laser technology would immediately knock 20 percent off the energy use. She also mentioned that these lasers could fire far more regularly than the existing hardware at the National Ignition Facility. Which gets into all the other problems that laser-driven fusion faces. Kim Budil, director of Lawrence Livermore National Lab, mentioned the other barriers. "This is one igniting capsule one time," Budil said. "To realize commercial fusion energy, you have to do many things; you have to be able to produce many, many fusion ignition events per minute. And you have to have a robust system of drivers to enable that." Drivers like consistent manufacturing of the targets, hardware that can survive repeated neutron exposures, and so on. So, while laser-driven fusion may have reached major energy milestones, there's a huge list of unsolved problems that stand between it and commercialization. By contrast, magnetic confinement in tokamaks, an alternative approach, is thought to mostly face issues of scale and magnetic field strength and to be much closer to commercialization, accordingly. "There's a lot of commonalities between the two where we can learn from each other," Ma said optimistically. "There's burning plasma physics, material science, reactor engineering, and we're very supportive of each other in this community. A win for either inertial or magnetic confinement is a win for all of us." But another speaker noted that magnetic confinement works at much lower densities than laser-driven fusion, so not all of the physics would apply. But Ma also suggested that, for laser-driven fusion to thrive, it may need to break away from its past in weapons testing. "Where we are right now is at a divergent point," she said. "We've been very lucky to be able to leverage the work that the National Nuclear Security Administration has done for inertial confinement fusion. But if we want to get serious about [using it for energy production], we need to figure out what an integrated system looks like... and what we need for a power plant. It has to be simple, it has to be high volume, it needs to be robust." None of those things had been required for the weapons work. Budil had the most optimistic take about the different approaches and uses, saying, "Many technologies will grow out of both fields, in addition to the path to a fusion power plant." John Timmer John became Ars Technica's science editor in 2007 after spending 15 years doing biology research at places like Berkeley and Cornell | ||

|

Step by step walk the thousand mile road |

USDOE is, like every other department under the Biden Administration, making bad news sound like it’s the best thing since sliced Mammoth using a highly spun headline. “… however, there's the uncomfortable fact that producing the 2 megajoules of laser power that started the fusion reaction took about 300 megajoules of grid power, so the overall process is nowhere near the break-even point.” So 300 megajoules in and two megajoules out equals a deficit of 298 megajoules (-300 + 2 = -298), and that doesn’t consider the energy needed to construct and operate the NIF, so the deficit is even larger. Nice is overrated "It's every freedom-loving individual's duty to lie to the government." Airsoftguy, June 29, 2018 | |||

|

| Wait, what? |

As long as the greenie retards can crow about saving the planet, the drumbeat to end the use of fossil fuels will continue, possibly even accelerate. Look at how they want everyone out of ICE vehicles and into full electric ones, despite the grid being in NO shape to support it. We are a long way from cold fusion saving anyone. “Remember to get vaccinated or a vaccinated person might get sick from a virus they got vaccinated against because you’re not vaccinated.” - author unknown | |||

|

| delicately calloused |

Pons and Fleischmann You’re a lying dog-faced pony soldier | |||

|

| Void Where Prohibited |

They've been saying that fusion would be sustainable in a few decades since I was a kid in the 60's. That was 60 years ago, and the forecast is still the same. "If Gun Control worked, Chicago would look like Mayberry, not Thunderdome" - Cam Edwards | |||

|

| Shit don't mean shit |

Several years ago Lockheed announced Skunk Works was working on a Compact Fusion Reactor (CFR), but I haven't heard any updates in quite a few years. Wonder if that work is still ongoing. | |||

|

| SIGforum's Indian Off the Reservation  |

A significant breakthrough, but still a long ways off from being a source of energy. Let me know when I can get one of these:  Mike You can run, but you cannot hide. If you won't stand behind our troops, feel free to stand in front of them. | |||

|

| Savor the limelight |

So the scientists fired a 2 megajoule laser at something that released 3 megajoules of energy, but 300 megajoules of grid power was used to create the 2 megajoule laser blast. That sounds like when my son’s swim team gets all excited about raising $800 selling concessions of donated food and drinks that cost $2,000. | |||

|

Don't Panic |

^^ From an engineering perspective, the efficiency is 3.15/300. So, yeah, cool, but .... | |||

|

| Member |

Lasers are typically 1% efficient, so they are a long ways from breaking even energy wise. -c1steve | |||

|

I Deal In Lead |

I spent a lot of years working in R&D on Opthalmic and neurosurgical lasers and they can approach 85% efficiency. So they run the whole gamut from highly inefficient to highly efficient. | |||

|

| Experienced Slacker |

I'd put at least even odds on it being so. Seems like they'd spend a couple bucks on such a thing at least... 52.6 Billion dollar black budget in 2022 | |||

|

| Peace through superior firepower |

Yeah, they said the same thing about the Segway  | |||

|

| Muzzle flash aficionado |

You're 129+ years old?  flashguy Texan by choice, not accident of birth | |||

|

| Peace through superior firepower |

Man, what? | |||

|

| Member |

Lots of energy went into a large experiment for a very tiny result. Good in the sense of a ratio of output per input, but the input was not fully accounted for when they ignored the energy used to produce that laser beams themselves. But for the narrow purposes of the experiment itself yea ! BUT, will simulating the core of the sun inside a fusion energy plant, along with the probabilities of forcing protons close enough to fuse enough to make such a plant practical (very small amount of the protons actually meet, since they are very small compared to the space they exist in, which is why our Sun burns instead of explodes), scale sufficiently given the size of the plant ? For now not close. But this apparent breakthrough in terms of conversion rate could be significant, IF it's true. There's all kinds of careers, funding, and the politics of funding at play here, including the standard practice exaggeration to protect all of that stuff in play. But here's the question: Can this experiment be replicated elsewhere ? Sure probably, as long as they didn't exaggerate too much to the point they're essentially lying. Can it scale ? I don't know, but they're not at that point yet beyond speculation. I see this sort of like a cure for cancer, finding the holy grail, that sort of thing. But it's fun anyway. Lover of the US Constitution Wile E. Coyote School of DIY Disaster | |||

|

| Void Where Prohibited |

I was eight years old in 1962. That's 60 years ago. How do you get 129? "If Gun Control worked, Chicago would look like Mayberry, not Thunderdome" - Cam Edwards | |||

|

| Member |

That's how he IDENTIFIES himself. Lover of the US Constitution Wile E. Coyote School of DIY Disaster | |||

|

Fighting the good fight |

Once he runs out of fingers and toes, flashguy don't count too good. | |||

|

| Savor the limelight |

By using each finger and thumb as a zero or one, you can count from 0 to 1,023 with just two hands worth of digits. 129 would be a thumb up on one hand and the bird on the other hand. | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata | Page 1 2 |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

SIGforum.com  Main Page

Main Page  The Lounge

The Lounge  US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

Main Page

Main Page  The Lounge

The Lounge  US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition

US Department of Energy announces achievement of significant milestone in fusion ignition© SIGforum 2025